|

A Replication of a Prosocial Reasoning Intervention for Juveniles

Norbert Ralph

Private practice, San Leandro, CA

[Sexual Offender Treatment, Volume 14 (2019), Issue 2]

Abstract

Aim/Background: A replication of a prior validation study was conducted using a workbook and relationship-based intervention which targeted prosocial reasoning in juveniles who sexually offended.

Material/Methods: The study sample consisted of 14 males, all in residential treatment for sexual offenses. The average age was 16.4. The ethnic breakdown was Hispanic 36%, Black 29%, White 29%, and Other 7%. Three counselor rating scales were used to assess outcomes. A pre/post test design was used. The intervention required training in the method for counselors and was completed in 10 individual sessions.

Results: A multivariate analysis found statistically significant pre to post test changes on all three counselor rating scales in a prosocial direction.

Conclusions: This study was a replication of a prior validation study, and consistent with the hypothesis that the workbook- and relationship-based intervention was related to positive changes in prosocial behaviors. However, replication of the results using more rigorous methodologies to rule out rival hypotheses is necessary.

Keywords: Adolescent, sexual offending, probation, treatment, outcomes, prosocial, psychosocial, maturity

In California, and similarly most of the United States, when a youth has sustained findings regarding a sexual offense, the disposition includes specialized treatment for sexual offenses. Since sexual offenses are among the most severe, and often cause significant harm to victims, a major concern in disposition planning for juveniles who sexually offended (JwSO) is to prevent any subsequent sexual or other reoffenses. Disposition planning ideally follows "best practices" guidelines (ATSA Adolescent Practice Guidelines Committee, 2017). The goal of effective treatment for JwSO has been described as "preventing recidivism and promoting the prosocial development of the youth" (p. 3) (California Coalition on Sexual Offending, 2013). The present article describes research regarding a treatment model designed to promote these outcomes. It is a replication of a validation study of a treatment method for JwSO, Being a Pro, which is also applicable with probation youth generally. This replication uses a new sample of JwSO and targets a risk factor for general and sexual recidivism, that is prosocial reasoning, using a model with evidence-based characteristics. The model is designed to be one component of treatment with probation involved youth. It is designed to address limitations of similar treatment models and consistent with "best practices" for treatment, including readily accessible training in the model. It also includes checks regarding implementing the model reliably, having a workbook based curriculum that helps insure fidelity, a theory-based treatment model promoting prosocial reasoning, an individually-based and affordable model which is relatively easy to implement, and while shorter than treatment alternatives, has a large enough treatment effect to justify the effort.

Recidivism Rates and Treatment Best Practices

The following literature review discusses the base-rate of recidivism for sexual offending for juveniles, effective treatment approaches, relevant developmental and brain-based research, and methods that promote prosocial reasoning in this population.

Estimation of recidivism rates is an important consideration in treatment planning JwSO. Caldwell (2016) reviewed recidivism rates for JwSO which had 33,783 subjects in 106 studies and a mean follow-up time of 58.98 months. In examining samples since 2000, he found on average a sexual recidivism rate of 2.75 percent and a total recidivism rate of 30 percent. Sexual recidivism was 1/10 the rate of recidivism for other offenses. This finding would imply that interventions to reduce nonsexual recidivism, in addition to sexual recidivism, would be important for JwSO. A similar position is discussed by Kettrey & Lipsey (2018) in their meta-analytic review of all available published and unpublished outcome studies of JwSO. They identified eight “high quality” studies based on their methodology which contrasted specialized JwSO treatment with "treatment as usual", that is treatments which would be used with a general probation population. They concluded that available evidence does not indicate that specialized programs for treating sexual offenses are more effective than general treatment within the juvenile justice system. They found that the treatment effect of specialized JwSO programs was greater on general recidivism than on sexual recidivism. Their research supported the conclusion that general treatments used for probation youth are as effective as specialized treatment models for this population.

An implication of the above research is that JwSO treatment should include "best practices" treatment for general juvenile recidivism. An authoritative review of this topic is by Lipsey and associates (Lipsey, Howell, Kelly, Chapman, & Carver, 2010) who used 548 different samples studying juvenile probation populations. They identified several factors connected with positive outcomes for treatment methods for juveniles on probation. The programs studied included model programs such as Functional Family Therapy, Multisystemic Therapy, and Aggression Replacement Training, which all had positive effect sizes, but so did others which were locally developed, and not more well-known "name brands." They found methods that used skill building and counseling, including those that promoted social reasoning, were the most effective. Complementary research showed that the fidelity with which programs are administered also has a large impact regarding their effectiveness. Interventions based on control or coercion only, were either ineffective, or counterproductive and resulted in worse outcomes. Programs were more effective if they were well-designed, faithfully implemented, and targeted at appropriate youth. Separate research by Tennyson (2009) and Goense, Assink, Stams, Boendermaker, and Hoeve (2016) showed program fidelity was strongly associated with positive program outcomes. The more faithfully a model is followed, the better the outcomes. For example, Goense et al. (2016) found in programs for juveniles with antisocial behavior a medium treatment effect-size when integrity was high (d=0.633, p < 0.001), but no significant effect when integrity was low (d=0.143, ns).

A model to describe programs that incorporated Lipsey's (Lipsey, et al., 2010) criteria, and literature on program fidelity, was described as "Evidence-based Program Characteristics" (EBPC) (Ralph, 2017). Factors in that model associated with positive program outcomes were: - Approaches that targeted social skills, problem-solving, and counseling.

- Treatments which are manualized to reliably implement the model.

- Training and supervision to promote fidelity to the model.

- Fidelity checks which are "baked in" and part of a model.

- Reliable pre/post outcome measures to assess treatment effectiveness.

Lipsey's (Lipsey, et al., 2010) and Goense's, et al. (2016) research indicates that programs having these characteristics are more likely to have positive treatment outcomes. This approach, focusing on "program characteristics" is an alternative to using "name-brand" approaches (for example, Aggression Replacement Training, Multisystemic Therapy, Moral Reconation Therapy, Functional Family Therapy etc.). As an analogy, an effective diet depends on having certain types of foods, in the right amount, not specific brands of foods.

Moral Reasoning and Brain Development during Adolescence

Stams et al. (2006) studied the relationship of moral reasoning to recidivism in juveniles. In a meta-analysis of 50 studies they found lower levels of moral judgment in delinquent youth compared to non-delinquents, and an almost large effect size (d=.76/AUC=.70). Effect sizes were larger for male offenders, older adolescents, those with low intelligence, incarcerated delinquents, and the use of production measures. Production measures obtained a sample of the youth's thinking, in contrast to choosing measures with fixed alternatives with specific answers or rankings. This research on general probation youth was also complemented by research showing developmental delays in JwSO, a subset of probation youth generally, regarding social reasoning. An instrument, the Prosocial Reasoning Outcomes (PRO) (Ralph, 2016a), which used vignettes, was used to assess two groups of JwSO in residential treatment compared to a sample of high school youth. The study found that JwSO youth were on average six years delayed in social reasoning compared to the sample of nonprobation youth. Youth with a higher risk of recidivism had lower levels of social reasoning. This finding suggests that immaturity in prosocial reasoning can help explain why one youth rather than another, similar in other respects, may engage in sexually harmful behaviors. Existing literature on the forensic implications of social reasoning more generally was summarized by Antonowicz and Ross (2005) reviewing both the juvenile and adult literature. They note:

"... a search of four decades of research literature on the relation between cognition and crime revealed a considerable body of empirical evidence that many offenders have experienced developmental delays in the acquisition of a number of cognitive skills that are essential to social adaptation" (p. 164).

Ralph (in press) has described neuropsychological research on brain development in adolescence and its relation to risk-taking and criminal behaviors. Adolescence is a period of rapid physical and sexual development. This period is usually complemented by less intensive supervision by adults, and for older adolescents, access to cars and mobility that may take them far from parental supervision. Risk-taking norms among peer groups, drug and alcohol use, and involvement with antisocial subcultures can further promote dangerous and harmful behaviors in adolescents. Adolescence is associated with the highest rates of accidents. Likewise, regarding criminal behaviors, in Canadian data, 17 is the age of highest incidence of those accused of property crimes, and age 13 the age of highest incidence of those accused of sexual crimes against children (Statistics Canada, 2016). A complementary view is by Bonner (2012) who described early adolescence as a high-risk transitory period for sexual offending due to the gap between sexual abilities and drive which for males are often present at age 13, and delays in social judgment.

Steinberg (2015), reviewing brain and behavioral research, describes adolescence as a period of plasticity in brain development relevant to the development of prosocial as well as antisocial behaviors. He presents evidence that in adolescence there is an increase in the drive or reward centers of the brain, risk-taking, and a complementary delay in the development of the judgment and control centers to regulate behavior and modulate impulsivity and risk-taking. The youth is simultaneously motivated to pursue rewarding activities using more risky behaviors to accomplish them, having greater physical/sexual abilities, and under less direct supervision of adults, while also waiting for controls over these behaviors to develop later in adolescence and early adulthood. The large treatment effect observed in the juvenile delinquency literature may relate to this plasticity. For example, one study found the treatment-effect size for juveniles receiving treatment for sexual offenses was -.51, compared to an adult treatment effect of -.14 in similar adult programs (Kim, Benekos & Merlo, 2015).

Kiehl's (2016) research on brain development used an fMRI for forensic and non-forensic populations. He compared the brains of juvenile males on probation with youth not on probation, and also average adults. He created a measure of "brain age" which allowed him to predict within a few months the chronological age of average youth with an algorithm developed from fMRI's. He found that juveniles on probation had brains that appeared 5 to 10 years less mature than juveniles not on probation. These differences appear to reflect immaturity in development, and not significant other differences or pathology in brain structure.

Ralph (in press) reviewed literature which identified that an increase in psychosocial maturity in juvenile serious offenders was associated with subsequent decreased criminal behaviors and also a diagnosis of psychopathy. For example, Steinberg, Cauffman, and Monahan followed 1,300 serious juvenile offenders for seven years after convictions. They created an instrument to assess psychosocial maturity that included measures of impulse control, aggression control, consideration of others, future orientation, personal responsibility, and resistance to peer influences. They found their measure of psychosocial maturity increased through age twenty-five consistent with current brain research. Levels of recidivism varied depending on psychosocial maturity. Less mature individuals were more likely to be persistent offenders, but also even those with a history of high-frequency offending who psychosocially matured were more likely to desist from criminal behaviors. A related study (Cauffman, Skeem, Dmitrieva, & Cavanagh, 2016) assessed the stability of psychopathy in 202 male juveniles and 134 adult males housed in secure detention facilities. The researchers used relevant versions of the Hare Psychopathy Checklist to assess psychopathy regarding traits including selfishness, callousness, impulsiveness, rule breaking, violence, and using others without guilt. They developed a measure of psychosocial maturity using a standardized set of self-rating scales. They found that increased psychosocial maturity predicted lower psychopathy scores in adolescents but not adults. Both the above studies suggest that with juveniles on probation, even in secure facilities, life opportunities and treatment to promote psychosocial maturation, should ideally be available to such youth which has the prospect of increased desistance from criminal behavior and reducing the assessment of psychopathic traits.

Treatments Which Address Moral and Prosocial Reasoning

Some effective methods for treatment of probation youth included in Lipsey's (Lipsey, et al., 2010) research were methods which targeted prosocial skills and reasoning in probation youth and addressed the delays in moral judgment documented in the Stams et al. (2006) research. One of the methods targeting prosocial skills and reasoning was Aggression Replacement Training (ART) which was validated in numerous studies with probation youth (Goldstein, Nensén, Daleflod, & Kalt, 2005). Several complementary approaches were developed including the Prepare Curriculum: Teaching Prosocial Competencies (Goldstein, 1999), and Thinking for a Change developed by Bush, Glick, and Taymans (1997). Amendola and Oliver (2010) reported ART was a "Model Program" for the United States Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention and the United Kingdom Home Office. They also note that it was classified as a "Promising Approach" by the United States Department of Education. Washington State found ART to be the most cost-effective treatment for probation youth (Washington State Institute for Public Policy, 2004). It should be noted, however, that approaches targeting other areas, such as family functioning, including Multisystemic Therapy, and Functional Family Therapy were also found to be effective (Lipsey, et al., 2010).

ART was used in three studies with JwSO and associated with favorable treatment outcomes (Ralph, 2012; Ralph, 2015a; Ralph, 2015b). A randomized trial (N=19) with juveniles in a residential setting showed quantitative improvement in psychological functioning that was also validated in qualitative focus groups (Ralph, 2012). This initial trial was replicated but included only an intervention group, and again the ART intervention was associated with positive outcomes, including psychiatric factors, caretaker reports of behavior, and production measures to assess gains in prosocial or moral reasoning (Ralph, 2015a). Qualitative analysis with focus groups post-intervention also supported a treatment effect. Youth in focus groups confirmed that the ART intervention helped them reduce emotional reactivity and make prosocial choices, and they would learn strategies some youth described colloquially as "check yourself before you wreck yourself." ART was also studied, again with a residential population (N=129) and those who participated had 1/4 odds of the risk of sexual acting out in the program (Ralph, 2015b). These studies were done with samples of convenience, looked at shorter-term psychological and behavioral outcomes rather than recidivism, but were consistent with a larger literature supporting the efficacy of ART with probation youth.

In summary, immaturity in social reasoning has been identified as a significant risk factor in criminal behaviors in juveniles, including JwSO. This immaturity can be understood as taking place in the context of brain development during adolescence, and that youth on probation show delays relative to other youth in this area. There is a complementary literature indicating there are effective methods to treat these developmental delays which can reduce recidivism and are associated with other positive outcomes, both for the general probation population and JwSO.

Being a Pro

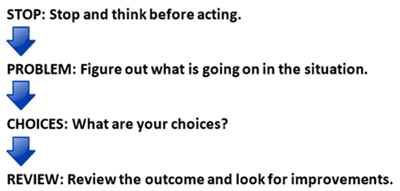

Ralph (2016b) developed a workbook and relationship-based treatment model, Being a Pro, which was influenced by the research described above. While the workbook and model are suitable for the general probation population, it was also developed with JwSO in mind, and filling a need for promoting prosocial skills and reasoning in this population. It is designed to be used as complementary to other treatment methods which can be included in existing programs. The treatment model is consistent with the research of Kettrey and Lipsey (2018) which suggested that best practices for treatment of JwSO might include interventions which promoted social reasoning to address developmental delays. The model of Being a Pro was influenced by the Moral Reasoning module of ART (Goldstein, et al., 2005) and Ralph's (2016a) research with the PRO measuring prosocial reasoning. For example, in the ART module, Moral Reasoning, youth are presented with some type of moral or judgment dilemma and asked to consider different responses and perspectives with the goal of considering and consequently developing more mature moral choices. The goal of such an approach is to give the youth one more prosocial perspective or choice than they had before. Youth might incorporate these new prosocial perspectives into their functioning and develop more prosocial relationships. The model for Being a Pro is described in Figure 1. The model was also developed using the criteria noted above of EBPC (Ralph, 2017) describing the characteristics of effective programs. Specifically, this required training and supervision in the method which verified competence in the model, and included both "baked in" fidelity checks, and treatment outcome measures. Further, it incorporated the literature regarding the importance of the treatment relationship in therapeutic change (Norcross & Lambert, 2011; Leversee & Powell, 2012), and the developmental literature that looks at the importance of identification, modeling, and scaffolding in child development (Watson, 2002). Training for use of the Being a Pro model has the counselor model a prosocial relationship with the youth. This provides the youth with a real-life example of prosocial behavior and increases their identification with the model. The prosocial counseling relationship with youth as well as the exercises in the workbook, were both viewed as important in promoting prosocial outcomes. The Being a Pro workbook was designed to be used in 10 sessions of individual therapy not only for JwSO, but the general juvenile probation population. The Being a Pro Model also includes PDFs of a Research and Theory Manual, a Therapist Manual (Ralph, 2016d; Ralph, 2016e), and an online training through PsychAcademy.net (Being a Pro, 2018) which all counselors in the present study were required to complete and demonstrate their competence by means of a posttest.

|

| Figure 1: Being a Pro Model |

Initial research was done with Being a Pro to see if it was associated with therapeutic outcomes (Ralph, 2016c). The sample for that study consisted of 39 youth on probation, all but one for sexual offenses, and all but one were males. The methodology used multiple informants (counselors and youth) and multiple methods (rating scales as well as production measures) in order to be comprehensive. Two production measures, three counselor rating scales, and one youth self-report were used. The two production measures obtained samples of the youth's prosocial thinking. A pre/post test design with one sample was used. A multivariate procedure found statistically significant prosocial changes hypothesized to be related to the intervention on five of six variables. The three counselor ratings all showed the largest effect sizes, larger than the production measures or youth self-report measure. The counselor ratings had large or very large effect sizes. Results were consistent with the hypothesis that the intervention promoted positive changes in prosocial reasoning and behavior using multiple informants and multiple methods.

One production measure used in this study which showed significant changes was the Washington University Sentence Completion Test (WUSCT). This provides a sample of the youth's thinking regarding interpersonal and emotional issues which assesses stages of ego development (Hy & Loevinger, 1996). This instrument has been used in over 350 studies and research supports the view of it as a stable measure of psychosocial maturity which increases with age, that stages are invariant for a given individual and stages can't be skipped, and is a stable measure with test-retests reliability greater than .80 (Westenberg, n.d.), and shows lower scores for JwSO compared to a non-clinical sample (Ralph, 2017). In the initial Being a Pro study, youth moved in the direction of increased psychosocial maturity regarding less manipulative and more rule governed behaviors. It is assumed that prosocial reasoning, the area targeted by Being a Pro, is a component of psychosocial maturity, and would be part of the personality functioning of the youth.

In summary, the Being a Pro model was developed with features and characteristics identified as consistent with the "best practices" literature and EBPC. It was designed as an inexpensive, easy to use, and turnkey model.

Method

Participants

Two samples were used, N=9, and N=5, for a total of 14, both residential programs for JwSO youth. All youth were referred for residential treatment by probation for adjudicated sexual offending charges, all were male, and the average age was 16.4. The ethnic breakdown was Hispanic 36%, Black 29%, White 29%, and Other 7%. These were "samples of convenience" from programs willing to participate. This was a new sample of youth, different from those described in the previous study (Ralph, 2016c).

Procedure

The Being a Pro workbook was used in one-to-one counseling. Counselors completed a 1.5-hour online training in the workbook. This included training in creating a prosocial therapeutic relationship since the role modeling of the therapist was an important factor in promoting prosocial change. They had to pass a test demonstrating competence in the model and workbook. The workbook itself provided exercises to challenge existing levels of prosocial reasoning and have the youth consider one more prosocial option or perspective in everyday situations. The workbook was used over 10 individual, one to one sessions, as part of the counseling. Counselors completed a Pretest before starting the workbook, and a Posttest after completing it, rating the youth's functioning. The workbook structure required that the model be used with fidelity, and fidelity checks are included in the workbook. The Being a Pro Model as implemented in this study was consistent with EBPC described above, incorporating Lipsey's (Lipsey, et al, 2010) criteria for successful programs.

Measures

A goal in the present research was to use a set of outcome measures that would take limited time and be easy to use, but also be effective in measuring a treatment effect-size. Instruments were selected based on the prior outcome research described above (Ralph, 2016c). In that study three measures completed by counselors had a large effect size. Three other measures using that study were completed by the youth which included two production measures and one self-rating scale. Two of those three measures had a statistically significant small to medium effect size, and one measure didn't show a significant effect size. Only the counselor rating measures were used in the present study. This smaller set of outcome measures was chosen not only because of larger effect sizes, but also because they required only about 1/3 of the time to complete compared to the full battery. Based on the author's research and clinical experience, using fewer measures made it more likely that they would be used in real life settings. Part of Being a Pro was to have a readily available and effective set of outcome measures that could be part of an easy to use, turnkey model. The smaller set of three counselor ratings were administered before the intervention (Pre) and after the intervention (Post). The measures are described below. In addition, a Likert-type rating scale completed by counselors was used to respond to the question, "Overall, did the workbook materials help improve prosocial reasoning skills for the youth?" The categories were Very, Somewhat, and Not Helpful.

IOWA Conners Scales

This test was completed by counselors and had two scales, and each had five items. The IOWA Conners Scales were the Aggression, and the Inattention/Overactivity scales. Loney and Milich (1982) reported test-retest reliability coefficients of 0.86 for Aggression, and 0.89 for Inattention/Overactivity. The scales have been used as an outcome measure in many studies including Ralph, Oman, and Forney (2001). These scales have an extensive research and normative basis. A decrease in scores indicates lower levels of impulsivity, inattention, uncooperativeness, and defiance, which reflect changes in a prosocial direction.

Prosocial Attitudes Questionnaire

The Prosocial Attitudes Questionnaire/Counselor (PAQ-C) was completed by the counselor before and after the intervention and rated the youth's prosocial thinking and behavior. This measure has 11 items. A decrease in this measure indicates changes in a prosocial direction. The development and psychometric properties of this instrument were discussed in the previous outcome study (Ralph, 2016c). In that study a Standardized Cronbach's Alpha assessed how each of the 11 items correlated with others and results were greater than .86 for both Pre and Post testing. A Spearman Correlation statistic was used to see if Pre and Post measures assessing the Being a Pro intervention correlated and indicated stability in the underlying trait. The Spearman value for the PAQ-C for this was .55 (P< 0.001).

Design

The design used was a one sample Pre/Post Test design. An assessment was done before the intervention and another after the intervention. This model has several limitations or threats to validity which include history/maturation, testing, and statistical regression.

Analysis

A multivariate procedure, the Hotelling Paired T-Test (Hintze, 2013) was used with the outcome variables to compare Pre and Post measures, and the significance of changes. The null hypothesis used in this analysis was that all differences from Pre to Post were zero or no change on any variable. If the analysis showed that the null hypothesis could be rejected, then a comparison of individual variables from Pre to Post could be conducted.

The Wilcoxon Test (Hintze, 2013), a nonparametric paired T-test, was used for Pre/Post test comparisons for each scale with a one-tailed test in the direction of the hypothesized change in a prosocial direction, and a .05 level of significance. An effect size was calculated for statistically significant results only.

In addition, for the PAQ-C, each item was analyzed for changes using the Wilcoxon Test, for Pre/Post test comparisons (Hintze, 2013) with a one-tailed test, and a .05 level of significance.

Results

The analysis comparing the Pre and Post scores, using the Hotelling Paired T-test is shown in Table 1 and the results showed P= 0.0046 using a randomization procedure which is more robust and can be used in small samples with ordinal data. The null hypothesis of no significant change on all variables from Pre to Post test could be rejected.

Table 1: Search Term Combinations |

| Hypothesis |

Hotelling’s

T2 |

DF1 |

DF2 |

Parametric

Prob levels |

Randomization*

Prob levels |

Means All Zero

N=14

|

27.613 |

3 |

13 |

0.0046 |

0.0046 |

| *The randomization test results are based

on 10,000 Monte Carlo samples. |

This significant overall result permitted comparisons of each outcome measure. The results using the Wilcoxon Test are in Table 2. All three outcome measures showed significant changes from pre to posttest in a positive direction indicating improvement, consistent with the hypothesis that the Being a Pro promoted such changes. An effect size was also calculated and indicated approximately a large or greater effect size for all measures.

| Table 2: Pre and Post Test Changes for Being a Pro |

| Outcome

variable |

N |

Pre mean |

Post mean |

Mean change |

SE of dif. |

Z-value

Wilcoxon |

P level |

Effect

size* |

Size |

| IO |

14 |

10.14 |

7.86 |

2.29 |

0.77 |

2.06 |

0.0196 |

0.75 |

Med-Large |

| AG |

14 |

9.93 |

6.29 |

3.64 |

0.91 |

3.12 |

0.0009 |

0.98 |

Large |

| PAQ-C |

14 |

3.96 |

3.29 |

0.68 |

0.2 |

3.02 |

0.0053 |

0.84 |

Large |

| * See: https://www.psychometrica.de/effect_size.html#transform |

In addition, the 11 items on the PAQ-C were analyzed in order to describe what specific types of changes in a prosocial direction were observed by counselors and the results are shown in Table 3. Such an ad hoc analysis, examining individual items, rather than total scales, should be considered exploratory. As can be seen in Table 3, items 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, and 9 reached significance at the .05 level or greater. Results indicated that youth after the intervention showed changes which can be summarized as increasing: 1. Cooperation with adults and rules, 2. Emotional control and regulation, 3. Resistance to peer pressure, and 4. Planning and thinking ahead. This list may be useful in understanding concretely what changes can be observed regarding prosocial development of probation youth generally and JwSO particularly as a result of treatment.

Counselors rated the impact of the Being a Pro intervention as either somewhat helpful (64.3 percent) or very helpful (35.7 percent).

| Items |

Pre mean |

Post mean |

Mean change |

SE of dif |

Z-value Wilcoxon |

P level |

| 1 Being ok with parents, teacher, or other adults telling them what

to do. |

3.79 |

2.79 |

1.00 |

0.26 |

2.89 |

0.00 |

| 2 Do things their own way instead of following rules |

3.64 |

2.79 |

0.86 |

0.35 |

2.20 |

0.01 |

| 3 They would rather get in trouble rather than be embarrassed in front

of my friends. |

3.36 |

2.57 |

0.79 |

0.35 |

1.98 |

0.02 |

| 4 If they can't get what I want, they just get mad. |

3.93 |

2.57 |

1.36 |

0.31 |

2.89 |

0.00 |

| 5 If someone is annoying or bothering they just ignore them. |

3.93 |

3.50 |

0.43 |

0.37 |

1.35 |

0.09 |

| 6 Acting aggressive when someone is aggressive to them. |

3.57 |

2.86 |

0.71 |

0.38 |

1.59 |

0.06 |

| 7 Thinking rules are usually stupid. |

3.79 |

2.79 |

1.00 |

0.30 |

2.74 |

0.00 |

| 8 Plans ahead to avoid problems. |

4.79 |

3.64 |

1.14 |

1.14 |

2.64 |

0.00 |

| 9 What parents or teachers think is more important than what friends

think. |

4.29 |

3.36 |

0.93 |

0.93 |

2.31 |

0.01 |

| 10 When others get mad at them, they let things cool off, and don't

get mad back. |

4.43 |

4.21 |

0.21 |

0.21 |

0.97 |

0.17 |

| 11 When things don't go their way, they can just let it go. |

4.14 |

3.79 |

0.36 |

0.27 |

1.23 |

0.11 |

| P <.05 in bold-italics. |

Discussion

This article presents a replication of a Pre/Post assessment of a workbook-based treatment approach for probation youth generally, and also JwSO. The treatment model was consistent with criteria associated with therapeutic outcomes for probation populations which was described as EBPC (Ralph, 2017). This included having a manualized workbook format and training regarding the method used to promote fidelity to the model. It also included built-in fidelity checks to assess compliance with the model, and outcome measures to assess whether there were in fact significant pre/post test therapeutic outcomes. The intervention, Being a Pro, showed statistically significant improvement on pre to post changes with measures of prosocial attitudes, aggression, and inattention. This is a replication of a prior research with this treatment model which showed similar outcomes with a different sample Ralph, 2016c). Item analysis of the measure of prosocial attitudes indicated that the greatest pre to post test changes were on items which measured cooperation with adults and rules, emotional regulation, resisting peer pressure, and planning ahead.

There is evidence to suggest that programs such as Being a Pro that target prosocial reasoning might be a valuable inclusion for at least one component of programs for JwSO. For example, Caldwell's study (2016) found that nonsexual recidivism in JwSO is 10 times that of sexual recidivism. Stams et al. (2006) identify moral or prosocial reasoning as one risk factor for juvenile delinquency. Treatment approaches which are designed to increase this factor have shown effectiveness with the general probation population (Amendola & Oliver, 2010) and also for JwSO (Ralph, 2012; Ralph, 2015a; Ralph, 2016c). The present study and the previous one (Ralph, 2016c) provide qualified information that the program, Being a Pro, promotes prosocial reasoning and behaviors.

Other approaches it should be noted are also available which target prosocial reasoning, including ART (Goldstein, Glick, & Gibbs, 1998), the Prepare Curriculum (Goldstein, 1999), Thinking for a Change (Bush, Glick, & Taymans, 1997). ART has a large literature indicating positive treatment outcomes (Amendola & Oliver, 2010). These approaches typically are done over a significant timeframe. ART, for example, takes 30 sessions, in contrast to Being a Pro which takes about 10 sessions. It would be presumed that longer treatment would produce a greater treatment effect, and these approaches would be preferable if circumstances permit. However, the use of ART, to take one example, while desirable if possible, has challenges. It requires the same cohort of four to eight youth to participate in an ongoing group for 30 sessions. In real life clinical situations now, given shorter times on probation, and less youth referred to residential settings, this goal is difficult to accomplish. Also, to be competent in the ART model requires counselors obtain three days of in-person training and significant agency start-up costs. Also, ART doesn't have built-in fidelity checks, trainings aren't easily accessible, and don't have "built in" outcome measures. The Being a Pro model was developed to be more flexible and to be administered individually, rather than in a group, and to take about 10 sessions. It has an online training with competency measures, built-in fidelity checks for the model, was relatively inexpensive with a workbook cost of $14 and other materials and online training free of cost. Also, the research from the previous (Ralph, 2016c) and present study appears to indicate that the treatment effect of this intervention was large enough to justify the effort.

More definitive research is desirable to further validate this model such as multiple randomized trials with JwSO, including by independent researchers. This would provide greater confidence in the robustness and effectiveness of the treatment model. It should be noted, however, that of the JwSO programs studied by Kettrey and Lipsey (2018), only one, Multisystemic Therapy, with one study, had a randomized trial. They only selected studies with adequate methodology which provided specialized treatment for JwSO to contrast with treatments for the general probation population, that is treatment as usual. The goal of evaluating a method with multiple well-designed randomized trials for JwSO populations, contrasting a treatment group with treatment as usual, while an appropriate goal, has not yet been achieved.

If the hypothesis is that Being a Pro promotes prosocial development, what is the underlying mechanism? As noted in the literature review, two components may contribute to the hypothesized changes. The first component is exercises in the workbook and counseling provided to challenge the youth's patterns of social reasoning. Moral or prosocial development is presumed to occur when the existing model or paradigm an individual uses has to account for situations where these rules don't seem to work and other rules work better. This is the model used in the Moral Reasoning module of ART (Goldstein, Glick, & Gibbs, 1998). Being a Pro uses a similar approach by having the youth consider one more prosocial choice or perspective in everyday dilemmas which are done through the counseling and exercises in the workbook. This is a dialectic developmental process and encountering exceptions leads to modifications of the individual's basic moral paradigms towards more sophisticated and effective models. The second component that presumably promotes prosocial reasoning in Being a Pro, is relationship-based. The development of a prosocial relationship and providing a model of prosocial behaviors also reinforces the teaching of the model. The training provided for Being a Pro specifically addresses developing a prosocial relationship with the youth. The changes in prosocial reasoning observed in the present and previous study (Ralph, 2016c) are presumed to be part of the development of the personality of the youth and stable. Conceptually prosocial reasoning is related to measure of a psychosocial maturity, the WUSCT (Hy & Loevinger, 1996) which is considered to be a stable measure of such development (Westenberg, n.d.). In the previous Being a Pro study (Ralph, 2016c) the WUSCT showed significant changes from pre-to post- assessment.

The study described here has several limitations. Most prominent is the Pre/Post measure one-sample design which doesn't control for several rival hypotheses, that is whether factors other than the treatment are better able to account for the changes observed. For example, all the youth were in residential treatment, and were the changes observed due to the therapeutic program, and not because they received Being a Pro? Also, there could be a tendency for counselors to want to validate their efficacy and rate posttest measures higher than pretest measures. Using a control group and a randomized design could rule out these and other causal factors. The present study had additional limitations. The study was done with a small sample size, N=14. The studies were conducted by the developer of the intervention, and not independent researchers. Also, while ratings of psychological change are useful, a valuable addition to the research design would be other measures such as total recidivism or other indices of behavioral problems or prosocial behaviors after discharge.

Resources for the treatment of probation youth generally, and JwSO specifically, are always finite. An important consideration is what options are the most cost-effective, have readily available training methods, modest start up time and costs, have methods to evaluate outcomes, and rated as helpful by counselors. The method described here for treating prosocial reasoning offers one option in this regard.

References- Amendola, M., & Oliver, R. (2010). Aggression Replacement

Training stands the test of time. Reclaiming Children and Youth, 19,

47-50.

- Antonowicz, E, & Ross, R. (2005). Social

problem-solving deficits in offenders. In M. McMorran & J. McGuire,

Eds. Social problem-solving and offending: evidence, evaluation and

evolution (pp. 91-102). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

- ATSA

Adolescent Practice Guidelines Committee. (2017). Practice guidelines

for assessment, treatment, and intervention with adolescents who have

engaged in sexually abusive behavior. Retrieved from http://www.atsa.com/Members/Adolescent/ATSA_2017_Adolescent_Practice_Guidelines.pdf

- Being a Pro: A prosocial treatment approach for at-risk youth (1.5 CE). (n.d.). Retrieved December 11, 2018, from https://psychacademy.net/product/being-a-pro-a-prosocial-treatment-approach-for-at-risk-youth/

- Bonner,

B. (2012). Don’t shoot: We’re your children. What we know about

children and adolescents with sexual behavior problems. Retrieved

February 20, 2017, from Boy Scouts of America, http://www.scouting.org/filestore/nyps/presentations/Children-with-Sexual-Behavior-Problems-Bonner.ppt

- Bush,

J., Glick, B., & Taymans, J. (1997). Thinking for a change:

integrated cognitive behavior change program. Longmont, CO: National

Institute of Corrections.

- Caldwell, M. F. (2016). Quantifying

the decline in juvenile sexual recidivism rates. Psychology, Public

Policy, and Law. Advance online publication. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/law0000094

- California

Coalition on Sexual Offending (2013). Guidelines for the assessment and

treatment of sexually abusive juveniles. Retrieved June 1, 2019 from https://ccoso.org/sites/default/files/Adol%20Guidelines.pdf

- Goense,

P. B., Assink, M., Stams, G. J., Boendermaker, L., & Hoeve, M.

(2016). Making ‘what works’ work: A meta-analytic study of the effect of

treatment integrity on outcomes of evidence-based interventions for

juveniles with antisocial behavior. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 31,

106-115.

- Goldstein, A. (1999). The prepare curriculum: Teaching prosocial competencies. Champaign, IL: Research Press.

- Goldstein, A., Glick, B., & Gibbs, J. (1998). Aggression Replacement Training. Champaign, IL: Research Press.

- Goldstein,

A. P., Nensén, R., Daleflod, B., & Kalt, M. (Eds.). (2005). New

perspectives on aggression replacement training: Practice, research and

application. John Wiley & Sons.

- Hintze, J. (2013). Number Cruncher Statistical Systems (NCSS) 2009. Kaysville, UT: NCSS.

- Hy, L.X., & Loevinger, J. (1996). Measuring ego development (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

- Kettrey,

H., & Lipsey, M. (2018). The effects of specialized treatment on

the recidivism of juvenile sex offenders: a systematic review and

meta-analysis. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 14(3), 1-27.

- Kim,

B., Benekos, P. J., & Merlo, A. V. (2016). Sex offender recidivism

revisited. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 17(1), 105-117.

- Kiehl,

K. (2017). Neuroscience, mental health and the law: Past, present and

future. Forensic Mental Health Association of California, 3/24/17,

Monterey, CA.

- Lipsey, M., Howell, J., Kelly, M., Chapman, G.

& Carver, D. (2010). Improving the effectiveness of juvenile justice

programs: a new perspective on evidence-based programs. Center for

Juvenile Justice Reform, Georgetown University.

- Loney, J.&

Milich, R (1982). Hyperactivity, inattention, and aggression in clinical

practice. In D. Routh & M. Wohaich, Advances in developmental and

behavioral pediatrics (pp. 113-147). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

- Norcross, J. C., & Lambert, M. J. (2011). Psychotherapy relationships that work II. Psychotherapy, 48(1), 4-8.

- Westenberg, M. (n.d.). Personality Development. Retrieved June 18, 2019, from http://personalitydevelopment-leidenuniversity.nl/instruments

- Ralph,

N., Oman, D., & Forney, W. (2001). Treatment outcomes with low

income children and adolescents with attention deficit. Children and

Youth Services Review. 23. 145-167.

- Ralph, N. (2012). Prosocial

interventions for juveniles with sexual offending behaviors. In B.

Schwartz (Ed.), The sex offender: Issues in assessment, treatment, and

supervision (pp. 18-29). Kingston, NJ: Civic Research Institute

- Ralph,

N. (2015a). A follow up study of a prosocial intervention for juveniles

who sexually offend. Sex Offender Treatment, 10(1).

- Ralph, N.

(2015b). A longitudinal study of factors predicting outcomes in a

residential program for treating juveniles who sexually offend. Sex

Offender Treatment. 10(2).

- Ralph, N. (2016a). An instrument for assessing prosocial reasoning in probation youth. Sex Offender Treatment. 11(1).

- Ralph, N. (2016b). Being a Pro. Burlington, VT: Safer Society Press.

- Ralph,

N. (2016c). A validation study of a prosocial reasoning intervention

for juveniles under probation supervision. Sex Offender Treatment.

11(2).

- Ralph, N. (2016d). Being a Pro Research & Theory Manual. Brandon, VT Safer Society Press, 2016.

- Ralph, N. (2016e). Being a Pro Counselor Manual. Brandon, VT: Safer Society Press, 2016.

- Ralph, N. (2017). Evidence-based practice for juveniles in 2017. Sexual Abuse (Blog). Retrieved December 8, 2018, from https://sajrt.blogspot.com/2017/05/evidence-based-practice-for-juveniles.html.

- Ralph,

N. (in press). Neuropsychological and developmental factors in juvenile

transfer hearings: prosocial perspectives. Journal of Juvenile Law

& Policy.

- Stams, G. J., Brugman, D., Dekovic, M., van

Rosmalen, L., van der Laan, P., & Gibbs, J. C. (2006). The moral

judgment of juvenile delinquents: A meta-analysis. Journal of Abnormal

Child Psychology, 34(5), 692-708.

- Statistics Canada. (2016). Young adult offenders in Canada, 2014 Young adult offenders in Canada, 2014. Retrieved from https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/85-002-x/2016001/article/14561-eng.htm

- Steinberg,

L. (2015). Age of opportunity: Lessons from the new science of

adolescence. Boston: Mariner Books, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- Tennyson,

H. (2009). Reducing juvenile recidivism: A meta-analysis of treatment

outcomes. (Doctoral dissertation, School of Professional Psychology

Pacific University, 2009). Retrieved from commons.pacificu.edu/spp/109.

- Washington State Institute for Public Policy. (2016). Benefit-cost results: justice. Retrieved April 11, 2017, from http://www.wsipp.wa.gov/BenefitCost?topicId=1

- Watson, M. (2002). Theories of Human Development. Chantilly, Virginia: The Teaching Company.

Author address

Norbert Ralph, PhD, MPH

Private practice

San Leandro, CA

norbert.ralph@yahoo.com

|