|

Risk Management of Youth Sexual Offenders: The Singapore Context

Ting Ming Hwa, Gerald Zeng, Chu Chi Meng

All based at the Clinical and Forensic Psychology Service, Ministry of Social and Family Development, Singapore

[Sexual Offender Treatment, Volume 13 (2018), Issue 1/2]

Abstract

The way in which youth sexual offenders is managed has implications for their rehabilitation. A balance has to be achieved between deterrence and prevention of recidivism, and the rehabilitation and reintegration of the youth into society. In addition to the risk factors, criminogenic needs and protective factors that influence their offending, the assessment and treatment of youth sexual offenders should also take their developmental needs into consideration. Singapore adopts an integrated strengths and risk-based approach, with the Risk-Need-Responsivity serving as the foundational guide for assessment and treatment of such offenders. Over the years, this approach and its associated programmes have also evolved and improved in response to findings from local research and evaluation.

Keywords: youth sexual offending, risk assessment, risk management, offender rehabilitation

Introduction

Over the past few decades, there has been increasing public scrutiny over how society should deal with sexual offenders, which has led to the practice of "populist punitiveness" in some jurisdictions whereby the punishment of the offender and prevention of recidivism take precedence over treatment (Appelbaum, 2009; Birgden, 2004; Birgden & Cucolo, 2011; Edwards & Hensley, 2001). However, there have also been recent judicial shifts towards providing sentencing options that punish the crime, but not the offender (Appelbaum, 2009). Such approaches allow for the rehabilitation of offenders who commit sexual crime through comprehensive treatment and reintegration (Appelbaum, 2009; Birgden, 2004).

The management of sex offenders is therefore a sensitive issue, with various jurisdictions having to find a balance between the prevention of harm to society and victims again and the protection and reintegration of the sex offender (Birgden & Cucolo, 2011). Achieving this balance is particularly crucial when managing youth sexual offenders. Contrary to perceptions that all sexual offenders are the same, or that they are "lifelong predators", these offenders do differ significantly in terms of the risks, needs, and protective factors that influence their offending (Appelbaum, 2009; Birgden, 2004).

This chapter first introduces Singapore's youth justice, and touches on how the philosophy of restorative justice is applied to youth offending to achieve a balance between deterrence and personal accountability and ensuring that programmes and opportunities for rehabilitation and reintegration are provided. The various pathways through which youth offenders can take through the justice system will also be presented. However, the majority of youth sexual offenders in Singapore are managed by the Ministry of Social and Family Development though, and the chapter will focus on the assessment and management of these youth by the Ministry, particularly through the Clinical and Forensic Psychology Service (CFPS), which provides specialised assessment and treatment to offenders. The chapter will also elaborate upon the implementation of the Risk-Need-Responsivity model which forms the foundation from which offender assessment and treatment is carried out. The effort to conduct empirically-based assessment and treatment via the integration of findings from local research and evaluation will also be detailed, before a final discussion on the future directions of the management of youth sexual offenders in Singapore.

Youth Justice in Singapore

Singapore is a city-state in Southeast Asia with a population of 5.54 million (Singapore Department of Statistics, 2016). As a former British colony, many statues in Singapore are based on English common law. Therefore, the way in which offences are defined are similar to that of other commonwealth jurisdictions.

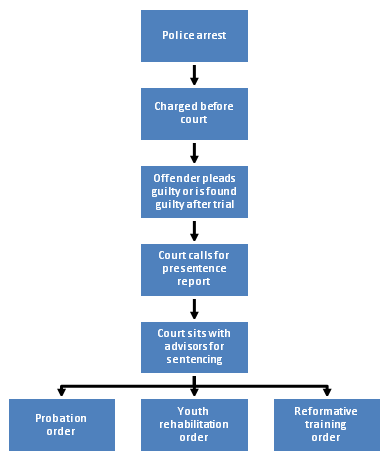

The pathway through the justice system that youth who sexually offended typically take is outlined in Figure 1. In Singapore, several legislations are pertinent to youth offending. The passing of the Family Justice Act in 2014 led to the formation of the Family Justice Courts, within which the Youth Court hears cases for offenders from seven up to 16 years of age (Family Justice Courts of Singapore, 2017). The Youth Court's jurisdiction is defined by Section 28 of the Children and Young Persons Act of 20011, which directs the Youth Court to consider the welfare of youth offenders while making judicial decisions (Family Justice Courts of Singapore, 2017; Singapore Statutes, 2001). A similar stance is also adopted by the Magistrates Court of Hong Kong. For instance, males below the age of 14 who have sexual intercourse with underaged females can be sentenced to receive treatment as part of their rehabilitation (Ng, Cheung & Ma, 2015).

|

| Figure 1: Legal pathways for youth offenders in Singapore |

The Singapore Youth Court adopts a philosophy of restorative justice, which seeks to achieve a balance between personal accountability for offences committed, and the rehabilitation of the offender with a view towards reintegration into family and community. It seeks to apply such a balance in its sentencing and programming by considering the availability of opportunities for the youth to acquire basic life skills, education, employability and self-sustenance while addressing the underlying causes of their offending. In doing so, the Court seeks to draw on available resources such as the youth's family to address problems in a holistic manner and enact meaningful change and reform in the youth (Family Justice Courts of Singapore, 2017).

In addition to these restorative justice programmes, the Youth Court may issue youth with several orders upon the finding of guilt. The Court first calls for a pre-sentence report to assist in sentencing. For the majority of youth offending cases, this is conducted by the Ministry of Social and Family Development (the Ministry), and considers various circumstances and risk factors such as family, education and/or employment, peers, gang membership, and antisocial attitude and behaviour of the youth. The pre-sentence report is taken into account by the Youth Court when it sits with two Panel Advisors2, Court counsellors, and a probation officer prior to sentencing. The Court has a number of options at its disposal, the most common of which are to issue a probation order, to commit offenders to a youth rehabilitation centre, or to undergo training at the Reformative Training Centre3. Youth who are placed on probation or ordered to reside in a youth rehabilitation centre are managed by the Ministry, whereas youth who are on reformative training orders are managed by the Singapore Prisons Service. However, the majority of youth who sexually offended are generally served with the former two orders, and so they are referred to the Ministry for management and treatment.

Profile and Typologies of Youth Sexual Offenders

The crime rate in Singapore is generally low at 588 crimes per 100,000 population (Department of Statistics Singapore, 2017). The youth crime rate is similarly low, and accounts for approximately 18-19% of all arrests in Singapore from 2011 to 2015 (Department of Statistics Singapore, 2017). With regard to sexual offending, the Singapore police encounters an average of 150 sexual assault cases and about 1,200 to 1,300 cases of molest annually (Seow, 2017). In the approximately 14 years from October 2002 to December 2011, 168 youth who sexually offended (aged 12 to 18 years of age) were referred to the CFPS for psychological assessment of risk of future sexually abusive behaviour. All the youth were male, and the majority were Chinese (44.3%, 74/167) or Malay (40.7%; 68/167); 12.0% (n = 20) were Indian, and 3% (n = 5) were of other ethnicity (Zeng, Chu, Koh, & Teoh, 2015).

The most common type of sexual offending was molestation (81.4%, 136/167), followed by voyeuristic (81.4%, 136/167) and exhibitionistic (81.4%, 136/167) offences. Only a minority of youth committed penetrative offences of nonconsensual fellatio 14.4% (n = 24), and 18.0% (n = 30) rape. Furthermore, the majority of youth sexual offenders tended to commit only sexual offending, only 33.5% (56/167) of the sample committed nonsexual offenses in addition to sexual offences (Zeng, Chu, Koh, et al., 2015). Among these youth, 18 (32.1%) had committed violent offences (e.g., rioting, robbery, causing harm), and 38 (67.9%) had nonviolent nonsexual offences (e.g., nonviolent theft, fraud, drug abuse). Delving into the typology of criminal diversity among youth who sexually offended, the same study found that youth who offended both sexually and nonsexually had higher risk and criminogenic needs as compared to youth who only sexually offended, specifically in terms of psychosocial functioning, peer relations, and engagement in recreational activities (Zeng, Chu, Koh, et al., 2015). Findings mirror those of a previous study that found youth who offended both sexually and nonsexually were more likely to reoffend violently, as compared to youth who only offended sexually (Chu & Thomas, 2010). Both studies therefore point to a distinction between youth who offended sexually and nonsexually and youth who offended only sexually, and suggest general criminogenic risk and needs may underpin the sexual offending committed by criminally versatile youth, which may result in a higher risk trajectory (Chu & Thomas, 2010; Zeng, Chu, Koh, et al., 2015). Hence, there is a need to ensure that interventions meet the risks and needs of the youth offenders as set out in the Risk-Need-Responsivity framework.

The Risk-Need-Responsivity Framework in Singapore

The Risk-Need-Responsivity (RNR) framework seeks to provide practitioners with accurate information and classification on risk and needs for effective rehabilitation to occur (Andrews & Bonta, 2010). The foundation of the RNR framework is the general personality and cognitive social learning theoretical perspective on offending behaviour, which suggests that eight major risk and need factors (the "Central Eight") are implicated in offending behaviour. Having a history of antisocial behaviour, antisocial cognition, antisocial personality patterns, and antisocial associates constitute the "Big Four" major risk factors, while family and marital relationships, poor education and/or employment circumstances, difficulties pertaining to substance use, and the absence of leisure or recreational activities make up the "Moderate Four" (Andrews & Bonta, 2010). The influence of the Central Eight on criminal behaviour has subsequently been supported by empirical studies and meta-analyses (e.g., Bonta, Law, & Hanson, 1998; Gendreau, Litte, & Goggin, 1996; Hanson & Morton-Bourgon, 2005; Lipsey & Derzon, 1998; McGuire, 2004).

The accurate identification and assessment of risks and needs such as the Central Eight can help practitioners to make an informed decision about the type of risk and needs to focus on, the level of treatment to be provided, and how to tailor intervention to suit the offender (Andrews & Bonta, 2010). These are expressed in three principles of the RNR model. The Risk principle states that the intensity of treatment should match the risk level of the offender. Hence, offenders assessed to be higher risk should receive more intensive supervision and treatment as compared to those with lower risk (Andrews, Bonta, & Hoge, 1990; Andrews, Bonta, & Wormith, 2011). The Need principle states that the intervention for each offender should focus on the specific dynamic criminogenic needs implicated in the offending behaviour. Finally, the Responsivity principle states the intervention and its delivery should match the offender's abilities and learning style. Altogether, these three principles of RNR ensure that resources and service delivery are appropriately and efficiently delivered to offenders in a manner that maximises their learning and rehabilitation (Andrews & Friesen, 1987; Andrews & Kiessling, 1980; Baird, Heinz, & Bemus, 1979; O'Donnell, Lydgate, & Fo, 1971). Furthermore, research has shown that interventions that incorporated the RNR principles have better outcomes in terms of the reduction in recidivism rates, as compared to interventions that do not employ the RNR principles (Andrews & Dowden, 2005).

In order to move towards empirically-based assessment and management of offenders in Singapore, the Ministry adopted the RNR framework in 2003 across the various Services that provide assessment and treatment services to adult and youth offenders (Chu, Teoh, et al., 2012). The introduction of the RNR framework led to significant changes in the assessment and management of offender. Key to the implementation was the introduction of the Level of Service instruments, which allowed for structured assessments of the Central Eight risk and need factors to be conducted, and produced risk classifications for targeted intervention and case management. As such, the Youth Level of Service / Case Management Inventory is currently used for the assessment of all youth offenders seen by the Ministry. Importantly, since its introduction, the RNR framework and the YLS/CMI has been gradually adopted by other government and nongovernment agencies that come into contact with youth offenders4. This has created a common language among such professionals, from which risks, needs and responsivity factors can be better understood and communicated (Chu, Teoh, et al., 2012; Chu & Zeng, 2017).

Stigma and Sex Offender Registry

Despite the adoption of the RNR framework in Singapore, which has helped greatly in the rehabilitation and re-integration of youth (sexual) offenders, it is necessary to acknowledge that stigmatisation may undermine such efforts. For instance, a survey conducted by Tan, Chu & Tan (2016) involving 628 undergraduate students who read a vignette illustrating a sexual, a white-collar, or a violent crime found that the level of stigmatisation directed towards sexual offenders was the highest. Similarly, research conducted in Hong Kong also showed that the public there also held a more negative view of sex offenders (Chui, Cheng & Ong, 2015). Hence, in view of such societal attitudes in Asian societies, there is therefore an added impetus to ensure that the treatment of youth sexual offenders is effective so as to reduce society's general desire for distance from such individuals, thereby helping them re-integrate into society.

In the Singapore context, all individuals "found guilty of committing a registrable offence" would have "a record of a conviction or sentence given by the courts" (Singapore Police Force, 2018). Therefore, the registry covers all individuals who commit registrable offences, and not just individuals who commit sexual offences. In other words, sex offenders are not singled for additional scrutiny. Additionally, access to conviction information is highly restricted, and they are not available in the public domain.

However, this is not necessarily the case in other Asian jurisdictions. For instance, Hong Kong introduced the Sexual Conviction Record Check (SCRC) scheme on 1 December 2011. Prospective employers can screen applicants whose jobs require them to have regular interaction with children and mentally incapacitated individuals with the register (Hong Kong Information Services Department, 2011). It was set up due to a spate of sex crimes committed against children in the late 2000s (Adorjan and Chui, 2012).

Adopting a slightly different approach, Malaysia introduced the Child Registry in 2017, a database containing information on the names of sex offenders and the offences they committed (Child (Amendment) Act 2016). However, official approval has to be sought from the Malaysian Ministry of Women, Family and Community Development (KPWKM) before access to the database is granted.

Treatment of Youth Sexual Offenders

After assessment of their risks, needs and strengths, youth sexual offenders may also be referred for treatment by CFPS. As with assessment, all group programmes and individual therapy provided by CFPS adopt a risk-based (RNR) approach that focus on relapse prevention while concurrently providing positive goals that youth can achieve (Chu & Ward, 2015). Psychologists work with the youth to openly explore and discuss the youths' risks, needs, and primary human goods, and how they have affected offending behaviour; additionally, internal and external strengths and capabilities are also identified (Chu & Ward, 2015; Thakker, Ward, & Chu, 2014). Intervention strategies and targets are then established, identifying the skills and capacities required to manage or mitigate the assessed risks and needs (Chu, Koh, et al., 2015; Chu & Ward, 2015).

Beyond Psychological Treatment and Intervention

Apart from psychological treatment and intervention, some Asian states such as South Korea and Indonesia have also introduced the use of mandatory chemical castration for certain convicted sex offenders in 2011 and 2016 respectively (Lee & Cho, 2013). Through the administration of anaphrodisiac drugs, it is expected that the sex drive and libido of the male sex offenders would decrease, thereby decreasing the likelihood of sexual reoffending. It is not a permanent solution since the effects are reversible when treatment ceases. However, Singapore has not considered this option which blurs the line between treatment and punishment, either for adult or juvenile sex offenders (Lee & Cho, 2013; Thibaut et al., 2016). At present, it adopts a rehabilitative approach focusing on the RNR principle in the management of sexual offenders, which has been found by Hanson, Bourgon, Helmus, and Hodgson (2009) to be effective in reducing sexual recidivism.

Future Directions

The regular evaluation and refining of treatment philosophy such as RNR are important for the provision of empirically-based services to youth sexual offenders. Research and evaluation studies should continue to examine the profiles of these youth in Singapore, validate existing assessment tools for local use, explore new instruments, and regularly evaluate treatment programmes. To this end, research initiatives are underway to conduct in-depth research into youth sexual offending. Notably, a longitudinal study was launched in 2016 to include all youth offenders in Singapore. The study, Enhancing Positive Outcomes in Youth and the Community5 (EPYC), is intended as a holistic examination of the interaction between youth offenders' developmental and offending trajectories. It examines a broad range of aspects such as risks, needs and protective factors, adaptive and maladaptive functioning, and adverse childhood experiences, so as to deliver insights that can improve on existing clinical and operational work.

Concurrently, CFPS is continually exploring interventions with not only with youth who sexually offended, but also with children and youth who are at risk of developing problematic sexual behaviour. For example, it is looking at adapting the evidence-based Problematic Sexual Behaviour-Cognitive Behavioural Therapy to specifically target inappropriate sexual behaviours among at-risk youth (Carpenter & Addis, 2000; National Institute of Justice, 2015). Additionally, CFPS will continue its ongoing programmes of professional training and attachment to specialist centres for its staff so as to keep up to date on the latest developments in sexual offending management and treatment.

References- Adorjan, M. and Chui, W.H. (2012) Children raping children: Contesting the innocence frame in Hong Kong. Youth Justice: An International Journal 12(3): 167-183, 10.1177/1473225412459834

- Andrews, D. A., & Bonta, J. (2010). The psychology of criminal conduct (5th ed.). New Jersey, NJ: Anderson.

- Andrews, D. A., Bonta, J., & Hoge, R. D. (1990). Classification for effective rehabilitation: Rediscovering psychology. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 17(1), 19-52. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854890017001004

- Andrews, D. A., Bonta, J., & Wormith, J. S. (2011). The Risk-Need-Responsivity (RNR) Model Does Adding the Good Lives Model Contribute to Effective Crime Prevention? Criminal Justice and Behavior, 38(7), 735-755. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854811406356

- Andrews, D. A., & Dowden, C. (2005). Managing correctional treatment for reduced recidivism: A meta-analytic review of programme integrity. Legal and Criminological Psychology, 10(2), 173-187. https://doi.org/10.1348/135532505X36723

- Andrews, D. A., & Friesen, W. (1987). Assessments of Anticriminal Plans and the Prediction of Criminal Futures A Research Note. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 14(1), 33-37. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854887014001004

- Andrews, D. A., & Kiessling, J. J. (1980). Program structure and effective correctional practices: A summary of the CaVIC research, 439-463.

- Appelbaum, P. (2009). Foreword. In F. M. Saleh, J. Grudzinskas, Albert, J. M. Bradford, & D. J. Brodsky (Eds.), Sex Offenders: Identification, Risk Assessment, Treatment, and Legal Issues. New York, NY, USA: Oxford University Press.

- Baird, S. C., Heinz, R. C., & Bemus, B. J. (1979). Project report #14: A two-year follow-up. Wisconsin: Department of Health and Social Services, Case Classification/Staff Deployment Project, Bureau of Community Corrections.

- Birgden, A. (2004). Therapeutic Jurisprudence and Sex Offenders: A Psycho-Legal Approach to Protection. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment, 16(4), 351-364. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:SEBU.0000043328.06116.ee

- Birgden, A., & Cucolo, H. (2011). The Treatment of Sex Offenders: Evidence, Ethics, and Human Rights. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment, 23(3), 295-313. https://doi.org/10.1177/1079063210381412

- Bonta, J., Law, M., & Hanson, K. (1998). The prediction of criminal and violent recidivism among mentally disordered offenders: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 123(2), 123-142. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.123.2.123

- Carpenter, K. M., & Addis, M. E. (2000). Alexithymia, gender, and responses to depressive symptoms. Sex Roles, 43(9-10), 629-644. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007100523844

- Child (Amendment) Act 2016. (2016). Retrieved from http://www.federalgazette.agc.gov.my/outputaktap/20160725_A1511_BI_WJW006870%20BI.pdf.

- Chu, C. M., Koh, L. L., Zeng, G., & Teoh, J. (2015). Youth Who Sexual Offended: Primary Human Goods and Offense Pathways. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment, 27(2), 151-172. https://doi.org/10.1177/1079063213499188

- Chu, C. M., Teoh, J., Lim, H. S., Long, M., Tan, E. E., Tan, A., ... Puay, L. L. (2012). The implementation of the Risk-Needs-Responsivity framework across the youth justice services in Singapore.

- Chu, C. M., & Thomas, S. D. M. (2010). Adolescent Sexual Offenders: The Relationship Between Typology and Recidivism. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment, 22(2), 218-233. https://doi.org/10.1177/1079063210369011

- Chu, C. M., & Ward, T. (2015). The good lives model of offender rehabilitation: working positively with sex offenders. In N. Ronel & D. Segev (Eds.), Positive Criminology. Abigndon, UK: Routledge.

- Chu, C. M., & Zeng, G. (2017). No Title. In H. C. (Oliver) Chan & S. M. Y. Ho (Eds.), Psycho-Criminological Perspective of Criminal Justice in Asia: Research and Practices in Hong Kong, Singapore, and Beyond. Routledge.

- Chua, J. R., Chu, C. M., Yim, G., Chong, D., & Teoh, J. (2014). Implementation of the Risk-Need-Responsivity Framework across the Juvenile Justice Agencies in Singapore. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 0(0), 1-13. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/13218719.2014.918076

- Chui, W.R., Cheng, K.K & Ong, R. Y. (2015). Attitudes of the Hong Kong Chinese Public Towards Sex Offenders: The Role of Stereotypical Views of Sex Offenders. Punishment & Society, 17(1), 94-113 . DOI: 10.1177/1462474514561712

- Department of Statistics Singapore. (2017). Latest Data. Retrieved March 6, 2017, from http://www.singstat.gov.sg/statistics/latest-data

- Edwards, W., & Hensley, C. (2001). Restructuring Sex Offender Sentencing: A Therapeutic Jurisprudence Approach to the Criminal Justice Process. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 45(6), 646-662. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X01456002

- Family Justice Courts of Singapore. (2017a). Youth Court Matters. Retrieved February 19, 2017, from https://www.familyjusticecourts.gov.sg/Common/Pages/YouthMatters.aspx

- Family Justice Courts of Singapore. (2017b). Youth Courts. Singapore. Retrieved from https://www.familyjusticecourts.gov.sg/QuickLink/Pages/Brochures.aspx

- Gendreau, P., Litte, T., & Goggin, C. (1996). A meta-analysis of the predictors of adult offender recidivism: What works! Criminology, 34(4), 575-608. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.1996.tb01220.xHanson, R. K., & Morton-Bourgon, K. E. (2005). The Characteristics of Persistent Sexual Offenders: A Meta-Analysis of Recidivism Studies. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(6), 1154-1163. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.73.6.1154

- Hanson, R.K., Bourgon, G., Helmus, L., & Hodgson, S., The Principles of Effective Correctional Treatment also Apply to Sexual Offenders: A Meta-Analysis, Criminal Justice and Behavior, 36(9), 865-891. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854809338545

- Hong Kong's Information Services Department (2011) Sexual Conviction Record Check Scheme to Receive Advance Appointments from November 28. Hong Kong SAR: Hong Kong's Information Services Department. Available at: http://www.info. gov.hk/gia/general/201111/27/P201111270170.htm

- Lee, J. Y., & Cho K. S. (2013). Chemical castration for sexual offenders: physicians' views. Journal of Korean Medical Science, 28(2), 171-172. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2013.28.2.171

- Lipsey, M. W., & Derzon, J. H. (1998). Predictors of violent or serious delinquency in adolescence and early adulthood: A synthesis of longitudinal research. In R. Loeber & D. P. Farrington (Eds.), Serious and Violent Juvenile Offenders: Risk Factors and Successful Interventions (pp. 86-105). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications. https://doi.org/doi: 10.4135/9781452243740.n6

- McGuire, J. (2004). Understanding Psychology and Crime: Perspectives on Theory and Action. Berkshire, UK: Open University Press.

- National Institute of Justice. (2015). Program Profile: Children with Problematic Sexual Behavior-Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (PSB-CBT). Retrieved from https://www.crimesolutions.gov/ProgramDetails.aspx?ID=380

- Ng, W.C., Cheung, M. & Ma, A.K. (2015). Sentencing Male Sex Offenders Under the Age of 14: A Law Reform Advocacy Journey in Hong Kong. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse 24(4), 333-53, 10.1080/10538712.2015.1022292

- O'Donnell, C. R., Lydgate, T., & Fo, W. S. O. (1971). The buddy system: Review and follow-up, 1, 161-169.

- Seow, B. Y. (2017, February). New one-stop centre for sexual crime victims after review of investigation, court processes: MHA. The Straits Times. Retrieved from http://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/courts-crime/new-private-centre-for-sexual-crime-victims-after-review-of-investigation

- Singapore Department of Statistics. (2016). Yearbook of Statistics 2016. Singapore. Retrieved from http://www.singstat.gov.sg/publications/publications-and-papers/reference/yearbook-of-statistics-singapore

- Singapore Police Force, (2018), Check Eligibility for Spent Record. Retreived from http://www.police.gov.sg/e-services/find-out/check-eligibility-for-spent-record

- Singapore Statutes. Children and Young Persons Act (2001). Singapore. Retrieved from http://statutes.agc.gov.sg/aol/search/display/view.w3p;page=0;query=DocId%3A911aba78-1d05-4341-96b7-ee334d4a06f0 Status%3Ainforce Depth%3A0;rec=0

- Tan, XX., Chu, CM., Tan, G. (2016). Factors Contributing Towards Stigmatisation of Offenders in Singapore. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 23(6), 956-969. https://doi.org/10.1080/13218719.2016.1195329

- Thakker, J., Ward, T., & Chu, C. M. (2014). The good lives model of offender rehabilitation: A case study. In T. O'Donohue, William (Ed.), Case Studies in Sexual Deviance. New York, USA: Routledge.

- Thibaut, F., Bradford, J. M. W., Briken, P., De La Barra, F., Habler, F., Cosyns, P, on behalf of the WFSP Task Force on Sexual Disorders. (2016). The World Journal of Biological Psychiatry, 17, 2-38.

- Zeng, G., Chu, C. M., Koh, L. L., & Teoh, J. (2015). Risk and Criminogenic Needs of Youth Who Sexually Offended in Singapore: An Examination of Two Typologies. Sexual Abuse : A Journal of Research and Treatment, 27(5), 479-95. https://doi.org/10.1177/1079063213520044

Footnotes

1In the Children and Young Persons Act, a "child" refers to a person who is below the age of 14 years and a "young person" refers to a person who is 14 years of age (or above) and under 16 years old.

2Panel Advisors are individuals from the community who have extensive experience in working with youth. Panel Advisors are appointed by the President of Singapore (Family Justice Courts of Singapore, 2017b).

3This option is only provided for youth who are 14 to 16 years of age.

4These include Government Agencies such the Ministry of Social and Family Development, the Singapore Prisons Service, the Central Narcotics Bureau, and the Singapore Police Force, as well as non-Government Agencies such as social service organisations. For more information, see Chua et al. (2014), and Chu and Zeng (2017).

5See https://www.researchgate.net/project/Enhancing-Positive-outcomes-in-Youth-Offenders-and-the-Community for project details.

Author address

Dr Gerald Zeng, PhD

Senior Manager & Senior Research Specialist

Clinical and Forensic Psychology Service

Ministry of Social and Family Development

Singapore

|